The Durutti Column \ Biography

Born in Higher Blackley, Manchester, in 1953, composer-guitarist Vini Reilly first found wide acclaim as the principal member of The Durutti Column, a constantly evolving modern music ensemble recruited by Factory Records in 1978. The original band soon splintered, leaving Reilly as the sole member. His first album, The Return of the Durutti Column, recorded with producer Martin Hannett in 1979, established the fragile, mercurial player as a major talent.

The Return of the Durutti Column (1979)

The Return... was recorded on eight track equipment at Cargo Studio, Rochdale, in August 1979. Martin Hannett produced, John Brierley engineered. 'At the time of the album I'd decided on a minimal thing,' recalls Vini. 'Where there'd be only one drum machine and one backing track, with one guitar tune over the top. Martin and I didn't sort of click together at first, but we worked as a team and I really liked him in the end. On the album he just played about with knobs, he's not at all technical [sic]. He got synthesized drums and things for me. Martin reproduces echoes, finds a rhythmic pattern on the synthesizer... Also, some of it was spontaneous. I gave him twenty tracks and he selected the ones he could work with best.'

'Someone at Factory decided it would be good idea to send Vini Reilly in to Cargo with Martin as an experiment,' adds John Brierley, who owned Cargo. 'I don't think Vini had any real ideas as to what he wanted to do, it was just sort of a solo jam session over three days to see what would happen. Over the first two days we recorded bits of stuff from Vini, who sat on the studio floor with his guitar. Martin had arrived with much more than his usual amount of effects, I had a job fitting it all in the control room then we spent what seemed an awfully long time connecting it all up and getting it all fed into the desk. In hindsight Martin should have been in studio two days before Vini arrived, one day to get all the gear in and connect it up and a second, because a lot of the gear was new to him, to work out how it all worked. While Martin and I were sorting all this out Vini was turning out ideas in the studio, Martin showed little or no interest in what Vini was doing. Basically I just kept the tape running.'

At the time Vini was being managed by Tony Wilson and Alan Erasmus, the two co-founders of Factory. Their charge was presented with a Gordon Smith custom guitar. 'Martin arrived with these great big black cardboard-fronted machines,' says Tony. 'Synthesizers. For two days, the Monday and Tuesday, Martin did nothing but create strange rhythm/noise tracks. Occasionally Vini would strap on the guitar and play some notes onto the tracks. But it was hard to get Martin to notice as he pored over the primitive electronics. By the second night Vini had had enough.'

'Occasionally Vini would come in to listen to playbacks and then back into the studio,' continues Brierley, 'but he got no feedback from Martin as to whether what he was playing was good, bad or indifferent. Martin was far too engrossed in his Time Modulators and AMS Digital units. But this was one of those occasions when Martin gave himself too much gear, too many options. Some of the gear was new to him and basically he just played around until by accident he came across a sound he liked. To me it seemed he really wasn't sure what he wanted, but if he tried enough combinations then by the law of averages something good would come up. Unfortunately he was so intent on finding these sounds that he completely ignored Vini. This eventually got to Vini, accumulating into a serious row between the two of them and Vini storming out. I didn't know what to say being caught in the middle. Vini was rightly saying that his music was the most important thing, Martin was saying that without his effects/production there was no album.'

'Sketch for Summer was made up in the studio because Martin managed to get these bird noises on the synthesizer,' remembers Reilly.

Hannett was typically cryptic. 'Durutti Column... The one with the tweety birds on it.'

The album was subsequently mixed at Strawberry in Stockport, technically a more sophisticated studio than Cargo. 'Martin had to find sounds to add where it didn't matter if the guitar was slightly in front or behind the backing,' adds Brierley. 'The main track on the album, Sketch for Summer, happened that way. It was impossible to put a strict tempo behind the guitar, so by chance Martin came across the bird sound which turned the track into something quite different and unique. The whole sound happened by accident. It wasn't planned, but maybe it worked better that way.'

The first 2000 copies of FACT 14 arrived in a heavy-grade sandpaper sleeve, an idea conjured by musician Dave Rowbotham and Tony Wilson, in turn inspired by Mémoires, a Situationist text by Guy Debord and Asger Jorn issued in a sandpaper wrapping in 1959. Sex Pistols designer Jamie Reid also influenced the project. Factory sourced their sandpaper sheets from Naylors Abrasives in Bredbury, and utilized surplus sleeves from printer Garrod & Lofthouse. 'I didn't know much about the sandpaper sleeve until I actually wandered into the Factory office to find Joy Division sticking sandpaper cards on old steam locomotive sound effects album covers,' says Reilly. 'I was very removed from all that.'

'I remember going with Bernard and Ian and sticking the sandpaper on that Vini Reilly record,' confirms Joy Division bassist Peter Hook. 'It destroyed all your other records. It was an amazing idea and only Factory would have done that. I loved Factory's attitude. No-one has ever emulated it.'

'Joy Division did about five hundred of them,' Tony Wilson elaborates, 'because Ian needed money more than the rest of them. The other three watched porn movies while Ian did all the slapping and pasting. The strange thing about wallpaper paste is that it looks rather like semen. Coming back to the flat at midnight, finding the other three staring at the porn video, and Ian slapping this semen everywhere, is one of those great memories.'

Factory design director Peter Saville was responsible for the labels alone. 'I hated the sandpaper sleeve,' he admits today. 'I always thought it should have been emery paper.'

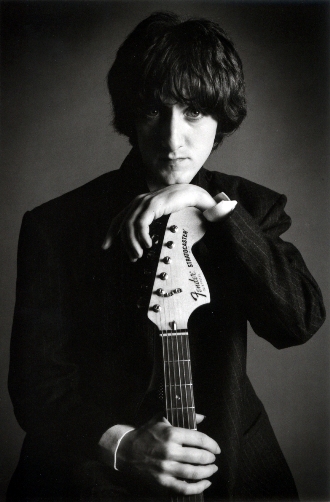

Wilson commissioned photographer Daniel Meadows to take some promotional portraits. 'At that time I was working at Granada TV as a programme researcher and occasional arts presenter. One afternoon Tony asked me to go with him to a flat in Didsbury (Alan Erasmus' place, I think) and photograph Vini. While I was there a group of people (I can't remember who, but Factory folk including members of Joy Division) were sitting round trying to work out how to assemble the sandpaper album sleeves. They had a kind of production line going and they got me to join in. For my pains they gave me an album. My copy has sandpaper both sides and, in silver capitals (we were experimenting using stensils and spray paint) on the front it has THE RETURN OF THE DURUTTI COLUMN and, on the back, FACT 14. I still have it.'

Reilly didn't actually hear his own debut album until he was handed a test pressing. 'I didn't really hear the album from playing the pieces until I got the white label. It took me years to realize that what Martin had done was to give the album as a whole an identity, which it would have lacked otherwise. It would have just been a few guitar tunes.'

1980 - Lotta Continua

Despite bouts of recurring illness, during the summer of 1980 Reilly and Hannett taped around 45 minutes of new material, albeit with no definite project in mind. Two of these tracks were earmarked as a single on new imprint Factory Benelux, pairing Madeleine with Lips That Would Kiss (Form Prayers To Broken Stone), the latter an homage to Ian Curtis and Annik Honoré. The electronic rhythm track on both was supplied by experimentalist Eric Random, formerly of the Tiller Boys, and also known as A Boy Alone. 'The next stage had to be replacing Martin Hannett's amazing electronic beat creations with the intimacy and personality of a live drummer,' argued Factory foreman Tony Wilson. 'Normally these things - drummers - are in ample supply, but 1980 was a busy year for Manchester bands. No spare drummers at all, it seemed.'

As well as The Durutti Column, Wilson and Factory co-founder Alan Erasmus also managed post-punk funk quintet A Certain Ratio. Their drummer, Donald Johnson, already knew Reilly well. 'Me and Vini go way back,' Donald recalls today. 'Well before punk and Factory Records we used to jam together before we were in any bands. We met through a mutual friend called Vinny Faal, who at the time used to put up all the gig posters around Manchester.' Live drums were added to three new Durutti tracks: For Mimi, For Belgian Friends and Self-Portrait - the latter described as 'not very kind! by Vini himself.

'I've always admired Vini's playing,' continues Johnson. 'He has a soft dexterity which can only be described as beautiful. I just remember being in the studio working on the arrangements, which was mainly me learning them on the day as we had no rehearsal prior to recording. Then we would record the drums in one take. Vini played his guitar with the exact reverb and delays he was going to use as my guide. I'm not sure if Vini overdubbed later or used the original guide tracks as the master.'

Although Hannett still occupied the producer's chair, these would be his last recordings with Reilly, released in December on the double album sampler A Factory Quartet (Fact 24). Indeed Reilly became the first Factory act to insist on working with a different producer. Since ACR were busy throughout 1980 most Durutti live shows took the form of short solo sets, with a rhythm track and additional guitar on tape. Reilly's first overseas performance was a Jean Cocteau-themed event at the Plan K venue in Brussels on 27 June, shared with Richard Strange, Richard Jobson and Bill Nelson. Nelson, who was in the process of upgrading his own equipment, agreed to sell Vini his old TEAC reel-to-reel machine. 'I'm getting a four track tape recorder,' Reilly told Sounds in July. 'On the new stuff I'll be playing bass and some piano, so it won't be so minimal. It'll be a bit more varied.'

Along with a handful of Factory package shows in London, and the second Futurama Festival in Leeds, Reilly also played as a member of the Invisible Girls behind Pauline Murray and John Cooper Clarke on a British tour in October, and performed a short interval set at selected dates (two tracks appear on the bonus 7" single included here). The Durutti Column were also booked to take part in a Factory package tour around the Low Countries immediately afterwards, billed with A Certain Ratio and Section 25, but for health reasons Reilly played only the larger shows, including Rotterdam, Den Haag and Brussels.

Towards the end of 1980 Reilly was commissioned to record a one-off single for highbrow French imprint Sordide Sentimental, which had previously issued limited edition packages by Joy Division and Throbbing Gristle. As with Lips That Would Kiss, the circumstances were uncommonly poignant. 'Jean-Pierre Turmel commissioned a piece of music from me for his very sick and dying girlfriend, Danny Dupic,' Vini explains. 'The record they had listened to as lovers was The Return of the Durutti Column, and I believe she did hear Danny before she died.'

The silver lining to this dark cloud was that SS 45005 brought Reilly together with a compatible drummer in the shape of Bruce Mitchell. "I spoke to Alan Erasmus," Vini recalls, "very unhappy about the drummers I worked with in the past because I knew they weren't right. Alan immediately said, 'What about Bruce Mitchell?' I'd seen Bruce around but I'd never really spoken to him properly. I was somewhat in awe of Bruce as a local character. He was very well known. I'd seen him play with the Albertos a few years previously, but I didn't know him."

The Albertos were Alberto Y Lost Trios Paranoias, a comedy rock band led by writer C.P. Lee. A relative veteran at 41, Mitchell had also backed John Dowie on the Factory Sample EP (Fac 2) and boasted a range of impressive jazzy chops. "Bruce lived on Central Road, just around the corner from the Factory office on Palatine Road. Alan immediately rang Bruce and said that I was going to come round to see him. That was the first time I'd actually properly spoken to Bruce, and before I'd even asked him about whether he would play drums for the single he just said to me in his usual style, 'It will be an honour and a pleasure.' And that was it. The die was cast. We were supposed to rehearse it but we ended up playing them once because Bruce just had them straight away. I realised very quickly that he didn't need rehearsing and in fact it would be a mistake to rehearse it too much."

"Vin was very easy to play with, no problem at all," agrees Mitchell. "The way he would play, the sequences would have an unusual logic. It wouldn't be strict in 4 or 8 bar formations, and his chord changes would just seem to happen in a different way. Plus he was running a lot of echoes, so my drums had to be about meter more than beat. And it had to go down very fast as Vini has a certain intolerance in the studio."

Danny and Enigma were recorded at Graveyard Studio on Church Lane in Prestwich, so called because the building overlooked a large cemetery. It was owned by Stewart Pickering, the studio itself being located in the basement of his home. Bruce made his live debut as one half of The Durutti Column somewhat later, at a private gig at the Lamplight Club in Chorlton, Manchester on 24 July 1981.

LC (1981)

Since the material on The Return of... was already 18 months old it was high time for a second album. Fortunately inspiration struck in the unlikely surrounds of a back bedroom on Pytha Fold Road, Withington. "I bought a 4-track TEAC reel-to-reel from Bill Nelson of Be Bop Deluxe, of all people," explains Vini. "It was knackered, it was a very old machine. I bought it off my own bat, just to muck around with. And one night, about three o'clock in the morning - I was staying at my mum's house, she was quite elderly - I went in the spare bedroom, and I just felt very inspired and I recorded for about five hours, with a very cheap drum machine, a Roland Space Echo and one guitar, and one very cheap microphone, and that's most of what your hear on LC. I didn't do it to make an album, I just did it because I was inspired. These things just arrive. There's no work involved. There's no cerebral, intellectual exercise. It's all simple, very simple, and it's played as it is in my head."

The night in question seems to have been sometime in March or April 1981, with around five tracks spontaneously recorded. "Next day Tony Wilson asked me could he have a listen. I had a very early Walkman, he listened to it - and he wouldn't give me my Walkman back. He carried on listening to it all afternoon. After a couple of hours he said, 'This is an album.' I said, 'I don't think it is'. But soon after we went into Graveyard, which was really built for jingles, but it meant that Bruce could add his drum kit and I put a piano down. I think we added some of my vocals. That's all that was added, and Tony said: 'That's great, that's an album'. I didn't really mind, I was quite happy about that. So if you listen to LC you'll hear hiss from the Space Echo, hiss from the quarter-inch tape, a very old tape that had been recorded over and over again. As far as audio people are concerned, sonically it was a joke. It's full of hiss and all sorts."

While some tracks on LC include elements of Vini's original bedroom demo, others were recorded (or re-recorded) from scratch. "I remember, unusually, liking the drums," Stewart Pickering recollects. "A beach ball bouncing on a pond type sound. They played everything pretty live and it went down very quickly. You had to make such quick decisions on 4-track. I ended up producing the album. It was very easy to do."

"LC went down very fast," confirms Bruce Mitchell. Indeed his appointments diary for 1981 confirms that the Graveyard session occupied just two days, 28 and 29 April. "It was pretty much recorded live. It was all stuff that Vin had in him, ready to roll out. Most things were second takes. The first pass would be a practise run, and the second it what you hear in the record. Even now, Vin really doesn't have a tolerance for not getting it down on tape immediately. Sometimes he'll spend a lot of time putting things down and then he doesn't like it. It's part of the process of the maestro, really. He just does it, and sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn't."

Undoubtedly the album works. "Once again Tony seemed to have the vision to realise that it could actually become an album with the right attitude," says Vini. "The whole thing was done in one day with Stewart Pickering and mixed in another half a day. So it was five hours, plus one day plus half a day. Afterwards it was clear to Tony - I presume - that there was a career for the Durutti Column, and that people were buying these albums."

There were even two outtakes: Mavucha, and the delightful Experiment in Fifth. One of three vocal tracks on LC, The Missing Boy, was Reilly's third homage to Joy Division singer Ian Curtis, after Lips That Would Kiss and Sleep Will Come the previous year. "It's an instant reaction," explains Vini, "because I spoke to Ian after his attempted suicide. That's why I called it that - he was missing, he never got to America. I knew him quite well, and I also knew his Belgian girlfriend, Annik, she became a friend of mine afterwards. She was one of the founders of Les Disques du Crepuscule and Factory Benelux."

In August of 1981 Reilly and Mitchell travelled to Brussels to play an open air show on the Muntplein( aka Place de la Monnaie). Interviewed for Belgian radio, Vini was asked to describe his music. "That's a really incredibly difficult question," he replied. "Its roots are based firmly in the new wave. There's an attempt at experimental things, and to redefine what should and shouldn't be rock and roll. The problem is that one has to use the same tools as the rock and roll people, it's very difficult to pick up a guitar and play through an amplifier loudly and to be original and creative, because so much has gone before. You're a victim of your environment. I wouldn't like to try and place my music anywhere, really. Call it new music, but not radical or unpleasant. I believe in elements of harmony and melody and blending them. Because there's no point in making a piece of music if people aren't able to listen to it. Stockhausen is a great example of that, he only reaches a very elitist core of people, who use their heads and not their souls."

"There are three basic responses to a piece of music - physical, intellectual and emotional. I try and incorporate each of them into my pieces, and at the same time try to be new and experimental. I don't know whether I succeed or not. I think what I'm churning out most of the time is trash. There's an odd spark occasionally which seems to work, more often than not by accident. So I get quite depressed about it sometimes, because I never know whether it's any good or not. It's not modern classical, no, because the phrase classical implies something that isn't in my music."

LC was released by Factory in November of 1981 with the catalogue number Fact 44. The outer and inner sleeves showcased several watercolour paintings by Jackie Williams, wife of Bruce Mitchell, and the dedicatee of album track Jacqueline. Already paintings were a regular theme in Durutti titles: Self-Portrait, Sketch for Dawn, Portrait for Frazier and Portrait for Paul, as well as two tracks issued on companion EP Deux Triangles: Favourite Painting, and Seascape for Zinnia (the original title of the track issued as Zinni). "Unbeknownst to me," says Vini, "Bruce had been playing the first album to Jackie, who is an artist, and she found it very inspiring to paint to. So it seemed logical to ask Jackie to do the sleeve for LC. It was done very quickly and it's one of my favourite sleeves."

Brian Eno declared a strong liking for LC. Surprisingly, however, Fact 44 received indifferent reviews in the British music press. "Wistful and positively reflective" offered NME, damning Reilly's masterpiece with feint praise and a single brief paragraph. Melody Maker displayed even less enthusiasm. "LC boasts the usual Reilly trademarks but never rises above the pleasant," wrote Lynden Barber. "It's at best merely pretty, at worst ineffectual. The lowest points are the four tracks where Reilly tries to sing."

When it came to Vini's fragile vocal style, Tony Wilson was of much the same mind. "Vini, the greatest guitarist in the known world, is now out of his bedroom, but he's taken up singing," Wilson wrote in 24 Hour Party People, an unreliable memoir published in 2002. "The band management stuff was going well..." Indeed Wilson often joked that he spent the next few years trying to persuade Simon Topping of A Certain Ratio to start singing again, and Vini Reilly to stop. "Let it be written, I failed miserably on both counts."

In truth, Vini's occasional vocals mesh well with the melancholy mood of his music, besides which flawed vocals became something of a Factory trademark. There is irony, also, in the title of the album, since LC stands for Lotta Continua, meaning 'the struggle continues' in Latin. Wilson claimed to have glimpsed it as wall graffiti in a television documentary on ancient Rome made by Anthony Burgess. Perhaps, but Lotta Continua was also the name of a far-left Italian political group active between 1969 and 1976 with a taste for 'spontaneous action'. Either way, oblique allusions to struggle seem misplaced, since the second Durutti album sounds effortless.

Dialogue and Triangles (1982)

1982 saw the release of a 12" EP on Factory Benelux, Deux Triangles, in similar vein to LC. As well as Favourite Painting and Zinnia the Benelux 12" also found room for a lengthy piano improvisation by Vini, originally recorded as a backing track for singer and poet Richard Jobson; some copies also included a bonus 7" featuring For Patti and Weakness & Fever. The group were also busy live, performing on Crépuscule's European package tour Dialogue North-South in February, opening Factory's Hacienda club in Manchester in May, and visiting North America for the first time.

On the Dialogue North-South tour Durutti performed in Amsterdam and Brussels, as well as their own headline show at Les Bains-Douches in Paris on 12 February. With Bruce Mitchell unavailable, Reilly began the tour with a rhythm loops before borrowing Marine drummer Alain Lefebvre for the remainder of the dates, Paris included. Crépuscule's multi-media jamboree also featured Paul Haig, Marine, The Names, Richard Jobson, Tuxedomoon, Antena and Isolation Ward, and was covered by writer Johnny Waller for British music weekly Sounds. Of Vini he observed: 'Backstage all the performers mill about casually, alternately unwinding after being onstage of preparing for the performance ahead, a can of beer or a comb in hand, a cigarette or a nervous joke on their lips. Vini Reilly looks in a permanent daze, even as you talk to him directly. As the Durutti Column he enjoys a degree of success, but all too often his mellow guitar exercises become overly soporific - especially in the Melkweg, where the smell of marijuana is literally stifling. But remembering his past illnesses it's a relief to hear him say "I'm well again" (even if the physical evidence doesn't corroborate that), "so I'm playing as much as I can now."'

'As I wandered off he was discussing the possibility of playing guitar accompaniment to Richard's poems, since Jobson's regular pianist, the classically-trained Cecile Bruynoghe, was unavailable. Such is the strength of this revue that the performers seem more willing to take chances.'

Another Setting (1983)

The second half of the year saw the completion of a new album, Another Setting, recorded at Strawberry with Hannett cohort Chris Nagle in the producer's chair. 'The new album is very different and very mixed,' offered Reilly at the time. 'It has brass sections and a lot of piano, the guitar's treated differently, and I'm muffing notes a lot. There's an old Hoagy Carmichael song on it. It's a strange arrangement, a really beautiful song.

The Carmichael classic in question was I Get Along Without You Very Well, sung by Lindsay Reade, sometime Factory employee and ex-wife of Tony Wilson. 'Did Tony think the song was a romantic message to him?' wonders Reade today. 'If it was, it was only subconscious. The truth (apart from the fact that I couldn't sing) was that I had been getting along without him very well - except perhaps in spring.'

The song was released as a 7" by Factory in June 1983, backed by exquisite instrumental track Prayer, featuring Cor Anglais by Maunagh Fleming. Both tracks broke new ground for Durutti and augured well for the album, which followed in August. Wilson, however, deemed the project largely unsatisfactory. 'Another Setting, while strangely providing some of the DC standards that Vin would be playing a decade later, merely trod the same ground as LC and took nothing forward. If in doubt, repeat yourself. It was time for a change.'

Reilly was also dissatisfied. 'I had this bunch of new songs where I was singing more and was a bit more dynamic, I felt. So Tony said, 'Sure', and I ended up going into Strawberry Studios, which is a very prestigious, big studio as you know. Very expensive studio. I spent a few days in there with an engineer called Chris Nagle who used to work with Martin Hannett as his engineer. But unfortunately the combination of myself and Chris Nagle was not a good one and it really killed the album. None of the reverbs were correct and it didn't sing. The guitar didn't sound good. Nothing sounded good. The entire album sounded very flat and I was incredibly disappointed with it. Tony was also. I think we all were. We had all the equipment you could possibly want and yet it sounded terrible.'

Short Stories For Pauline (1983)

Easily the most important composition by Vini in 1983 was A Little Mercy (aka Duet aka La Douleur), soon expanded to form the basis of an entire album, Without Mercy. A superlative instrumental for piano and violin, A Little Mercy seems first to have been recorded as Duet at Brussels studio Daylight Studio in November, when Reilly recorded an entire album called Short Stories for Pauline. On this version Vini was accompanied by Tuxedomoon violinist Blaine L. Reininger, who also guested on several other tracks, as did returning drummer Alain Lefebvre, harp player Anne Van Den Troost, and various horn players. Other stand-out tracks taped for Short Stories included Snowflakes (aka A Room in Southport) and The Sea Wall (aka College).

At the same time Reilly and Lefebvre undertook a short Belgian tour with poet Anne Clark, performing a short Durutti set before backing Clark on seven songs. Reilly had already collaborated with Clarke for side two of her album Changing Places, issued by Red Flame that same year.

Despite being allocated a catalogue number (FBN 36), Short Stories for Pauline remained unreleased. While undoubtedly better than Another Setting, it seems that Tony Wilson quickly recognised the potential of A Little Mercy and pushed to expand the piece into an entire 'orchestral' album, Without Mercy, released as the fourth Durutti album by Factory in June 1984. Thus Short Stories remained on the shelf in Brussels, although tracks were extracted for various compilations, notably a tribute to writer Marguerite Duras issued only in Japan. Reininger reprised his violin parts when Without Mercy was recorded in Manchester, and guested with an enlarged Durutti ensemble when the album was premiered in London at Hammersmith Riverside Studios in August 1984. Short Stories finally emerged in complete form as an archive vinyl and CD release on Factory Benelux in 2012.

Two lesser Durutti Column albums also slipped out during 1983. Live at the Venue was an official bootleg, released in June, while Amigos En Portugal was a patchy collection of studio offcuts released by Fundacao Atlantica in November. The latter found space for yet another version of A Little Mercy, this time titled Nighttime Estoril. Thankfully the relationship between Crépuscule and Durutti Column survived the complications around Short Stories for Pauline, with the band taking part in a Musique Epave tour of Japan in April 1984 with Mikado and Winston Tong, and a date at Crépuscule cafe Interferences. The next visit to Japan, in April 1985, would result in a live CD album and laserdisc, Domo Arigato.

Circuses & Bread (1986)

In 1985 the band recorded a new album, Circuses and Bread, released by Factory Benelux on vinyl (FBN 36) in April 1986, with a CD via Factory in June. The album was preceeded in March by a single (FBN 51), coupling Tomorrow with a superior non-album instrumental, All That Love and Maths Can Do, featuring viola player John Metcalfe. A later CD reissue of Circuses and Bread in 1993 on Crépuscule (TWI 988) somehow reversed the title and replaced the original 8vo artwork with a lesser design based on a 1930 poster by Herbert Beyer.

The final collaboration between Durutti and Crépuscule came exactly ten years later, when the label released another new studio album, Fidelity. Released as TWI 976 in April 1996, the set was recorded in Manchester and featured only Reilly, together with guest vocalist Elli Rudge. An atypical album, showcasing programmed beats and electronics over Vini's signature guitar playing, Fidelity was compared unfavourably with the albums which came before and after - Sex & Death (1994) and Time Was Gigantic (1998) - but remains a favourite for many Durutti aficionados.

Indeed Reilly, who suffered a series of strokes between 2010 and 2011, confesses to some bemusement at continued interest in his classic back catalogue. "I can't hear whatever it is that people are hearing in it. All I hear is me messing about, and that's it."

"It's all I've ever done. It's hard to explain. I get a piece of music in my head. You know when you play a piece of music, it's a series of events that take place over a space of time. When I hear a piece of music - when one arrives in my head from wherever, it's not like that, it's complete, a beginning, a middle, an end, it doesn't happen over a space of time. It's complete in itself. It just exists in my head - I plug my guitar in and tap into it, and play it. I don't need to rehearse it, I don't need to work it out or practice it. I just play it. In that sense, it's not improvised, it's complete in its entirety in my brain. Then once I've done it, I've lost all interest in it, it's done. Then I'll go to the next little point in my head which is another complete piece of music. It doesn't make any sense. I can't really explain it very well. That's the best I can do."

![The Durutti Column - Treatise on the Steppenwolf [FBN 63]](../images/fbn63.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - The Return Of The Durutti Column [FBN 114]](../images/fbn114.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - The Return of the Durutti Column [FBN 114 CD]](../images/fbn114cd.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - L.C. [FBN 10 / CD]](../images/fbn10cd.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - L.C. [t-shirt]](../images/lctee1.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Deux Triangles Deluxe [FBN 100]](../images/fbn100.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Another Setting [FBN 30 CD]](../images/fbn30cd.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Short Stories for Pauline [FBN 36 / CD]](../images/fbn36r.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Without Mercy [FBN 84 / CD]](../images/fbn84.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Domo Arigato [FBN 52]](../images/fbn52.jpg)

![Circuses & Bread [FBN 154 / CD]](images/fbn154.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - The Guitar and Other Machines [FBN 204 / CD]](../images/fbn204.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Vini Reilly + WOMAD Live [FBN 244 / CD]](../images/fbn244.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Obey The Time [FBN 274 / CD]](../images/fbn274web.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Sex and Death [FBN 201 / CD]](../images/fbn201.jpg)

![Fidelity [TWI 976]](../images/twi976.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Treatise on the Steppenwolf [FBN 63 CD]](../images/fbn63cd.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - M24J (Anthology) [FBN 164 / CD]](../images/fbn164.jpg)

![The Durutti Column - Postcard Box Set [FBN 56]](../images/durutticardbox1.jpg)